If there is someone who epitomizes The Mariachi Miracle it is Richard Carranza.

If there is someone who epitomizes The Mariachi Miracle it is Richard Carranza.

In so many ways his life and work, and that of his twin Reuben, symbolize the transformative power of youth mariachis. Earlier this week Richard was named Chancellor of New York City Schools, putting him in charge of America’s largest school district.

Press links:

Trying Again, de Blasio Names a New Schools Chancellor

Next to Lead New York’s Schools: An Educator With a Song on His Lips

New New York City chancellor also plays mariachi, sings

Tucson native Richard A. Carranza is picked to lead NYC’s public schools

As Richard has demonstrated in key school administrative roles in Las Vegas, San Francisco, and most recently Houston, leadership, respect, cultural sensitivity, community engagement and sheer inspiration of youth are tools every administrator needs to guide public education and build a better future for all. In days when a political administration seems intent on destroying public education and browbeating minorities, we need 1,000 Richard Carranzas to demonstrate that public education is far from over. It’s just getting its second wind.

Carranza was a social studies teacher at the high school he himself graduated from – Pueblo High School in Tucson, Arizona – when he started Mariachi Aztlán de Pueblo High in 1992. At the time, the mostly Mexican American Pueblo was one of the Tucson Unified School District’s poorest performing schools with high dropout rates, low graduation rates, and serious gang involvement. The school’s students were likewise from one of the most economically depressed in the city.

But Carranza was on a crusade to change all of that. For him, creating Mariachi Aztlán was more than starting a musical group. He understood its symbolic and actual power. He gave it the name Aztlán for a reason. Aztlán is the name of the legendary ancestral home of the Aztec people. He wanted young Mexican American men and women to know that they were not second-rate citizens but the descendants of a proud indigenous culture that dominated Mesoamerica.

Carranza understood that the way to inspire youth was to challenge them. It wasn’t enough to play well in the mariachi or look sharp in the traje – the suit of Mexico’s “charros” (gentlemen cowboys) that has become the uniform of the mariachi. He demanded good grades of his young musicians, knowing they were not just capable of achieving that goal but in fact would rise to the occasion. He made clear that every bad action of any of its members reflected back on the group, the school and the community. Get in a scuffle with the law and you are out.

Carranza made Mariachi Aztlán a symbol of pride for the Mexican American community, for Pueblo High Scholl and for all of the city of Tucson. Within a couple of short years, the group dominated the competition and continues to this day to be among the top youth groups in a city that has come to embrace mariachi culture as a living symbol of its own history and accomplishment.

More than that, Carranza put his young musicians on the path to college, drilling into them the idea that their earning power, their life potential and their ability to transform the American experience of their families could be so enhanced by getting that piece of paper. And he brought everyone along with him in that dream. Teachers, administrators, parents, community members.

Everyone.

He gave his young musicians the tools they would need to succeed in any life endeavor of their choice. He taught them teamwork, discipline, public speaking skills, critical thinking skills and more. He taught them who they are and where they come from. And in the process, he made them a force to be reckoned with, both onstage and off.

In a few short years, Pueblo’s graduation rate doubled, its dropout rate was way down, gang involvement dropped and a school considered a low performer was suddenly the model for how to get things done.

His focus was as much on young women as men. He saw their equal potential and recognized their unique position in society and Mexican culture as catalysts of change.

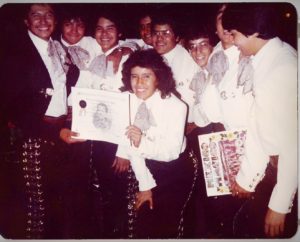

This was hardly new for Carranza. As a young boy his parents created a youth mariachi called Mariachi Nuevo, in which both he and his brother Reuben participated. The group was patterned after Tucson’s original youth mariachi – Los Changuitos Feos – in that it would charge for its performances, invest the money and send each graduate to college.

Many families in the Mexican American community couldn’t otherwise afford a college education for their kids. The vision that youth mariachis could become a vehicle to a college education was and is the key miracle in the youth mariachi movement.

Mariachi Nuevo was an excellent group, but also and innovator. Up to that time, youth mariachis in Tucson reflected the Mexican tradition of the mariachi as an all-male enterprise. But Mariachi Nuevo recognized, quite practically, that there were a number of young women playing their instruments as well as or better than their male counterparts. It was time for a change, and this seemed like a no brainer.

Not long after Mariachi Nuevo started recruiting young women, Los Changuitos Feos followed suit, and today throughout Tucson’s many youth mariachis in schools and private groups, a mixed male and female group is the norm. And like their male counterparts, these young women are taking advantage of the college scholarship opportunity to carve out their own destinies as scientists, engineers, doctors, lawyers and many other professions.

So many of these formative experiences make Richard Carranza the man he is. When he and Reuben arrived at Davis Elementary School for kindergarten, neither spoke English. Their parents were fluently bilingual but chose to only teach the boys Spanish so that they would always be able to talk with their cousins on the other side of the U.S. / Mexico border. They knew the boys were very bright and would pick up English quickly in school. And participating in Alfredo Valenzuela’s Mariachi Aguilitas de Davis Elementary School helped form their bilingual brains and give the brothers their first taste of their cultural heritage.

They grew up in South Tucson in a typical Mexican American neighborhood. Their friends in school were other Mexican Americans, Native Americans, African Americans and others. Their dad worked construction, their mother as a beautician.

Both boys excelled in school. Reuben became student body president at the University of Arizona and went on to become a vice president of Proctor and Gamble before creating his own Luxury Brands Partners hair and beauty aids company.

Like Richard, Reuben too is a man with a mission. So often beauticians like his mom are the first line of defense for women. They are the ones who hear first about spousal abuse, money problems, substance abuse and more. Reuben and his company work with people in the beauty industry around the country to make them agents of change who understand community resources and can put women in need in touch with the people and agencies that can best help.

Seeing Richard in action is to understand how in 25 years he rose from being a social studies teacher starting a mariachi to become the head of the largest school system in America. The work is personal to him at every level, and he is dedicated to it and to validating everyone he meets.

As he himself notes, it was the experience of creating Mariachi Aztlán that made him determined to become an educational administrator. Along the way, Carranza encountered all manner of institutional and personal racism, and had roadblocks thrown in his path. But he jumped every hurdle and overcame every obstacle. And in the end, those in the school music programs that mocked his effort were forced to recognize that his group had mastered style, unity, intonation and become virtuoso players beyond what most of the rest in the district had been able to achieve. And on top of that, he had inspired a generation and set the standard for those to come.

A few years back, while superintendent of schools in San Francisco, Richard decided to start a mariachi program. San Francisco had a very different ethnic makeup from Tucson with far more Central Americans, African Americans, Asians and Anglos than Mexican Americans. But he knew the infectious power of the music and its ability to transform lives.

He called the current director of Mariachi Aztlán in Tucson – John Contreras – and asked him to bring the group to San Francisco to show the fledgling San Francisco program members how good they would become. For nearly a week, the Tucson mariachis toured the city and performed for elementary, middle and high schools groups, before having a community performance on Friday night.

Carranza’s first encounter with that generation of Aztlán members told the story. At the time they were having lunch in a middle school cafeteria. He shook the hand of each group member, and their parent chaperones. He sat at a table with the Aztlán players and started asking them about where they planned to go to college and what they wanted to do when they graduated. He quietly impressed upon them how important it was that they seize that opportunity.

He continued to similarly meet and chat with the parents when at one point he noticed the school custodian folding table and stacking them along the wall. He excused himself, put his suit jacket on a chair, and joined the custodian in putting away the tables and chairs.

That level of humanity was on display everywhere on that Aztlán tour. He greeted the female African American bus driver who shuttled the kids around like family, posing with her and her fellow bus drivers and getting the scoop on how an ailing family member was doing. At every school he knew each teacher, administrator, aid and support crew member, greeting each warmly and asking about their programs.

At several of the schools and at the community concert on Friday night, Carranza picked up an instrument and performed with Aztlán, sometimes as soloist, others as just an ensemble element.

It’s not fake. It’s who he is.

It’s not fake. It’s who he is.

We saw it again on television last summer when he was superintendent of schools in Houston, Texas, and the hurricane hit just before schools were to open. Carranza was among the first responders, turning district schools into shelters and lending a personal touch to those struggling in the wake of the disaster. He got the schools open for business in record time to give families is crisis some sense of normalcy, and on the first day rode to school on the bus with a young African American student.

Carranza may not have been NYC mayor Bill de Blasio’s first choice for school chancellor but the mayor is about to find out how lucky he was to have gotten him. Carranza is a man of courage, wisdom, vision, and humanity. He is someone who will listen and work with teachers, administrators, students and the whole community to make the educational system of New York City a model for the world.

– Daniel Buckley, 03/08/18